Introduction

Git is an open-source distributed version control system that makes collaborative software projects more manageable. Many projects store their files in a Git repository, and platforms like GitHub have made code sharing and contribution accessible, valuable, and effective.

Open source projects hosted in public repositories benefit from contributions from the wider developer community through pull requests, which request that the project accept changes you have made to its code repository.

This tutorial will guide you through making a pull request to a Git repository via the command line so you can contribute to open source software projects.

Prerequisites

You must have Git installed on your local machine. This guide will help you check if Git is installed on your computer and walk you through the installation process for your operating system.

You will also need to have or create a GitHub account. You can do this through the GitHub website, github.com, and either log in or create your account.

As of November 2020, GitHub removed password-based authentication. For this reason, to access GitHub repositories via the command line, you will need to create a personal access token or add your SSH public key information.

Finally, you need to identify an open source software project to contribute to. You can learn more about open source projects by reading this introduction.

Create a copy of the Repository

A repository, or repo for short, is essentially the root directory of a project. The repository contains all of the relevant project files, including documentation, and also stores the edit history of each file. On GitHub, repositories can have multiple collaborators and can be public or private.

To work on an open source project, you first need to get your own copy of the repository. To do this, you need to fork the repository and then clone it to have a local working copy.

Fork the Repository

You can create a repository on GitHub by navigating your browser to the GitHub URL of the open source project you want to contribute to.

GitHub repository URLs refer to both the username associated with the repository owner and the repository name. For example, DigitalOcean Community (username: do-community) owns the cloud_haiku project repository, so the GitHub URL for that project is:

https://github.com/do-community/cloud_haikuIn the example above, do-community is the username and cloud_haiku is the repository name.

Once you've identified the project you want to contribute to, you can navigate to the URL, which is formatted like this:

https://github.com/username/repositoryOr you can search for the project using the GitHub search bar.

When you are on the repository home page, a Fork button will appear at the top right of the page, below your user icon:

Click the Fork button to begin the forking process. You will receive a notification in your browser window that the repository you are forking is being processed:

After the process is complete, your browser will go to a page similar to the previous repository page, except that at the top you will see your username before the repository name, and in the URL you will also see your username before the repository name.

So, in the example above, instead of do-community/cloud_haiku at the top of the page, you will see your username/cloud_haiku and the new URL will look like this:

https://github.com/your-username/cloud_haikuWith the repository forked, you are ready to clone it to have a local copy of the codebase.

Simulate the Repository

To create your own local copy of the repository you want to contribute to, we'll first open a terminal window.

We use the git clone command along with a URL that points to your repository fork.

This URL will be the same as the URL above, except it now ends with .git. In the cloud_haiku example above, the URL would read something like this, with your username replaced by your actual username:

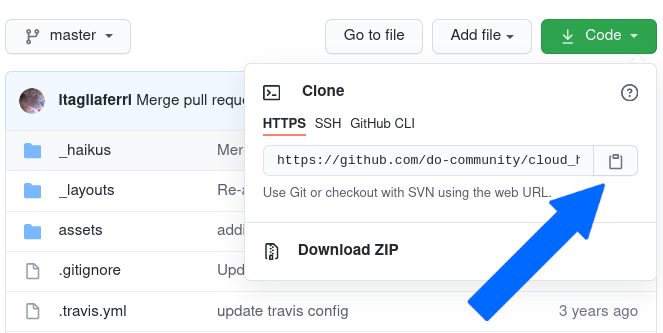

https://github.com/your-username/cloud_haiku.gitYou can also copy the URL using the green «⤓ Code» button from your repository page that you have separated from the main repository page. After clicking the button, you can copy the URL by clicking the clipboard button next to the URL:

Once we have the URL, we're ready to clone the repository. To do this, we combine the git clone command with the repository URL from the command line in a terminal window:

git clone https://github.com/your-username/repository.git

Create a new branch

Whenever you work on a collaborative project, you and other developers contributing to the repository will have different ideas for new features or fixes at the same time. Some of these new features won't take a significant amount of time to implement, but some will take a while. For this reason, branching the repository is important so that you can manage the workflow, isolate your code, and control which features make it back to the main branch of the project repository.

The initial branch of a project repository is usually called the master branch. A recommended practice is to consider everything in the master branch deployable so that others can use it at any time.

Note: In June 2020, GitHub updated its terminology to refer to default source code branches as master branches, rather than master branches. If your default branch still appears as master, you can update it to master by changing the default branch settings.

When creating a branch based on an existing project, you should create your new branch from the parent branch. You should also make sure that your branch name is descriptive. Instead of calling it my-branch, you should use something like frontend-hook-migration or fix-documentation-type instead.

To create a branch from our terminal window, we change our directory to work in the repository directory. Be sure to use the actual repository name (such as cloud_haiku) to change to that directory.

cd repository

Now, we'll create our new branch with the git branch command. Make sure to give it a descriptive name so that others working on the project know what you're working on.

git branch new-branch

Now that our new branch has been created, we can work on it using the git checkout command:

git checkout new-branch

After entering the git checkout command, you will receive the following output:

Output

Switched to branch 'new-branch'You can also compress the above two commands by creating and switching to a new branch, with the following command and the -b flag:

git checkout -b new-branch

If you want to revert to the original state, you use the checkout command with the original branch name:

git checkout main

The checkout allows you to switch between multiple branches, so you can work on multiple features at the same time.

At this point, you can now modify existing files or add new files to the project in your branch.

Making changes locally

To demonstrate creating a pull request, we'll use the cloud_haiku repo example and create a new file in our local copy. Use your favorite text editor to create a new file so we can add a new haiku poem as explained in the help instructions. For example, we can use nano and call our sample file filename.md. You should call your file by its original name with the extension md. for Markdown.

nano filename.md

Next, we'll add some text to the new file, following the help instructions. We'll need to use the Jekyll template and add a haiku with broken lines. The file below is a sample file, as you'll need to provide an original haiku.

--- layout: haiku title: Octopus Cloud author: Sammy --- Distributed cloud <br> Like the octopuses' minds <br> Across the network <br>

Once you have entered your text, save and close the file. If you are using nano, do this by pressing CTRL + X, then Y, then ENTER.

Once you have modified an existing file or added a new file to your chosen project, you can stage it in your local repository, which we can do with the git add command. In our example, filename.md, we would type the following command.

git add filename.md

We passed the name of the file we created to this command to stage it in our local repository. This ensures that your file is ready to be added.

If you are looking to add all the files you have changed to a specific directory, you can stage them all with the following command:

git add .Here the dot or dot adds all the relevant files.

If you are looking to recursively add all changes, including changes in subdirectories, you can type:

git add -A

Or, you can type git add -all to stage all new files.

By staging our file, we want to commit the changes we made to the repository with the git commit command.

Making changes

The commit message is an important aspect of your code contribution. It helps maintainers and other contributors fully understand the change you made, why you made it, and why it matters. In addition, commit messages provide a historical record of changes to the project as a whole, helping future contributors along the way.

If we have a very short message, we can capture it with the -m flag and the message in quotes. In our example of adding a haiku, our git commit might look something like the following.

git commit -m "Added a new haiku in filename.md file"

Unless it's a minor or expected change, we might want to add a longer commit message so that our collaborators are fully informed of our contribution. To record this longer message, we run the git commit command, which opens the default text editor:

git commit

When you run this command, you may find that you are in the vim editor, which you can exit by typing :q. If you want to configure your default text editor, you can do so with the git config command and set nano as the default editor, for example:

git config --global core.editor "nano"

or vim:

git config --global core.editor "vim"

After running the git commit command, depending on the default text editor you are using, your terminal window should display a document for you to edit that will look something like this:

# Please enter the commit message for your changes. Lines starting

# with '#' will be ignored, and an empty message aborts the commit.

# On branch new-branch

# Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/new-branch'.

# Changes to be committed:

# modified: new-feature.pyBelow the introductory comments, you need to add the commit message to the text file.

To write a useful commit message, you should include a summary on the first line, about 50 characters long. In this section, broken down into digestible sections, you should add an explanation that explains why the change was made, how the code works, and additional information that will make it clear to others who will review the work when merging. Try to be as helpful and proactive as possible to make sure those maintaining the project can fully understand your contribution.

Pushing changes

Once you have saved and exited the commit message text file, you can check what Git committed with the following command:

git status

Depending on the changes you made, you will get output similar to the following:

Output

On branch new-branch

nothing to commit, working tree cleanAt this point, you can use the git push command to apply the changes to the current branch of your forked repository:

git push --set-upstream origin new-branch

This command will provide you with output to inform you of the progress and will be similar to the following:

Output

Counting objects: 3, done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done.

Writing objects: 100% (3/3), 336 bytes | 0 bytes/s, done.

Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0)

To https://github.com/your-username/repository.git

a1f29a6..79c0e80 new-branch -> new-branch

Branch new-branch set up to track remote branch new-branch from origin.You can now go to the forked repository on your GitHub web page and navigate to the branch you pushed to see the changes you made in the browser.

At this point, it is possible to request a pull to the main repository, but if you haven't done so already, you need to make sure your local repository is up to date with the upstream repository.

Update Local Repository

While you're working on a project with other contributors, you need to keep your local repository up to date with the project, because you don't want to submit a pull request for code that will automatically cause conflicts (although in shared code projects, conflicts are bound to occur). To keep your local version of the codebase up to date, you need to sync changes.

First, we will configure a remote control for the fork and then synchronize the fork.

Configure a remote control for the fork

Remote repositories allow you to collaborate with others on a Git project. Each remote repository is a version of the project hosted on the Internet or a network that you have access to. Depending on your user privileges, each remote repository should be available to you as read-only or read-write.

To be able to sync changes you make in a fork with the main repository you are working with, you need to configure a remote that points to the upstream repository. You only need to set up the remote once in the upstream repository.

Let's first check which remotes you have configured. The git remote command will list any remote repositories you've previously specified, so if you clone your repository as we did above, you'll at least get output for the source repository, which is Git's default name for the cloned directory.

From the repository directory in your terminal window, let's use the git remote command with the -v flag to display the URLs that Git has stored along with their corresponding remote short names (like "origin"):

git remote -v

Since we simulated a repository, our output should look similar to this:

Output

origin https://github.com/your-username/forked-repository.git (fetch)

origin https://github.com/your-username/forked-repository.git (push)If you have already set up more than one remote, the git remote -v command will list them all.

Next, we specify a new remote repository to sync with the fork. This will be the original repository that we forked from. We will do this with the git remote add command.

git remote add upstream https://github.com/original-owner-username/original-repository.git

For our cloud_haiku example, this command would be as follows:

git remote add upstream https://github.com/do-community/cloud_haiku.git

In this example, upstream is the short name we provided for the remote repository, because in Git terms, “upstream” refers to the repository we cloned from. If we want to add a remote pointer to a collaborator’s repository, we might want to provide that collaborator’s username or a shortened alias for the short name.

Using the git remote -v command again from the repository directory, we can verify that our remote pointer has been correctly added to the upstream repository:

git remote -v

Output

origin https://github.com/your-username/forked-repository.git (fetch)

origin https://github.com/your-username/forked-repository.git (push)

upstream https://github.com/original-owner-username/original-repository.git (fetch)

upstream https://github.com/original-owner-username/original-repository.git (push)Now you can refer to upstream on the command line instead of typing the entire URL and you are ready to sync your fork with the main repository.

Sync the fork

Once we have configured a remote that references the upstream and master repository on GitHub, we are ready to sync our repository fork to keep it up to date.

To sync our fork, from our local repository directory in a terminal window, we use the git fetch command to fetch the branches along with their corresponding commits from the upstream repository. Since we used the short name “upstream” to refer to the upstream repository, we pass that to the command.

git fetch upstream

Depending on the number of changes that have been made since we forked the repository, your output may vary and may include multiple lines counting, compressing, and unpacking objects. Your output will end up similar to the lines below but may vary depending on the number of branches in the project:

Output

From https://github.com/original-owner-username/original-repository

* [new branch] main -> upstream/mainNow, commits to the main branch are stored in a local branch called upstream/main.

Let's go to the local master branch of our repository:

git checkout main

Output

Switched to branch 'main'Now we merge any changes made to the main branch of the main repository, which we will have access to through our local upstream/main branch, into our local master branch:

git merge upstream/main

The output here will be different, but it will start with an update if there have been changes made or if it is already up to date. If there have been no changes made since you forked the repository.

Your fork's master branch is now in sync with the upstream repository, and the local changes you made are not lost.

Depending on your workflow and the amount of time you spend making changes, you can sync your fork with the upstream code in the main repository as often as makes sense for you. But you should definitely sync your fork right before you make a pull request to make sure you don't automatically push conflicting code.

Pull Request

At this point, you are ready to submit a pull request to the main repository.

You need to go to your fork repository and press the new pull request button on the left side of the screen.

On the next page you can change the branch. On each side, you can select the appropriate repository from the drop-down menu and the appropriate branch.

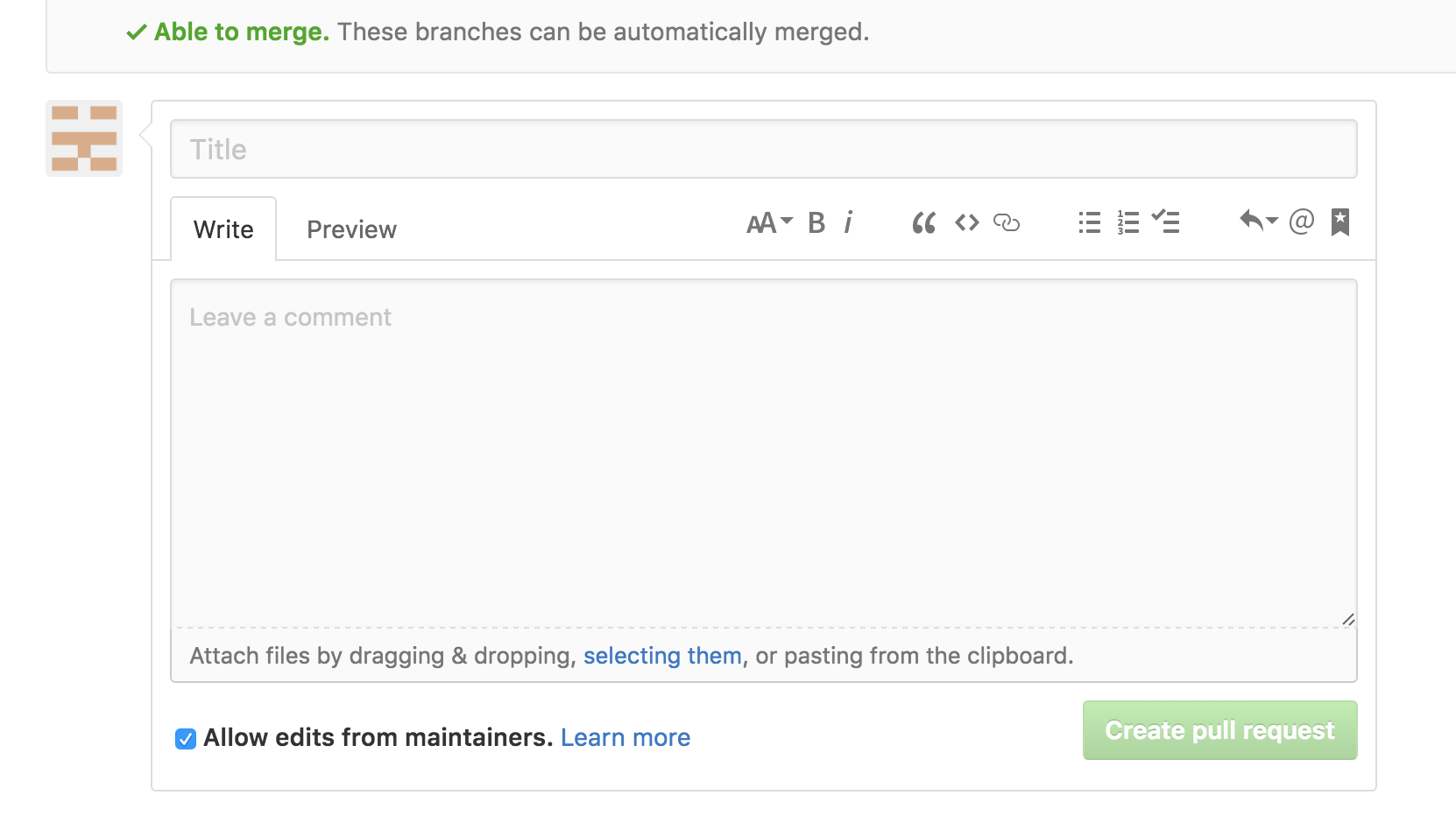

For example, when you select the main repository branch on the left and your new forked repository branch on the right, you should get a screen indicating that your branches can be merged. If there is no competing code:

You need to add a title and a comment to the corresponding fields and then press the Create pull request button.

At this point, the main repository maintainers will decide whether to accept your pull request or not. They may ask you to edit or fix your code by submitting a code review before accepting the pull request.

Result

At this point, you have successfully submitted a pull request to an open source software repository. After this, you should make sure to update and change your code while you wait for it to be reviewed. The project maintainers may ask you to rework your code, so you should be prepared to do so.

Participating in open source projects – and becoming an active open source developer – can be a rewarding experience. Regularly contributing to software you use frequently allows you to ensure that it is as valuable as possible to other end users.